She loved learning, as do I, but in really different ways. She tried to nudge me into taking college courses with her and reading beyond my mystery-escape-fiction tendencies. She got her doctorate in I'll say some kind of chemistry when she was in her sixties and was deservedly proud of it. After that she began to learn Pashto, and got so involved in the history and culture of Afghanistan that she spent a year there teaching. Then she had a book published about her experiences there.

Penny was my closest friend for a dozen years or so. She was my support system, and for someone like me who can be insecure and at times thin-skinned, I never EVER felt judged by her. As I sit here, I remember her cynical half-grin, sitting at Seanachie with her bottle of beer or glass of pinot grigio, sometimes sharing but mostly listening. Because she was the only drinking buddy I have had since college.

We got together almost like clockwork, every two or three weeks, for drinks and often dinner, although the dinner part appealed to me more than to Penny. She told me she had no sense of smell and that was why food had little attraction for her. Ironically, she liked to cook and talk about food, and try new things -- more so than I did. She would sometimes find a food at a restaurant that she liked so much she would go back over and over again until she suddenly tired of it and never wanted to go there again. If she had a meal she didn't like the first time she went to a restaurant, it was likely she would refuse to go there ever again, despite reviews and raves from friends.

Penny was comfortable meeting and getting to know people of all kinds in all settings. She enjoyed sitting at a bar and casually chatting with people she didn't know. When she made what we all considered a disastrous move from the lively Folly Beach to isolated rural Meggett, she found the one bar, where possibly no liberal had ever set foot, and became a regular. She told hilarious stories about debates at the bar, not unlike the crew at Donald E. Westlake's fictional O.J. Bar and Grill, where John Dortmunder and his unlikely gang of thieves met to plan their heists. I bugged her to put the stories in writing, but sadly, she did not. We worried about her safety, but apparently she held her own.

I, on the other hand, will go into a restaurant or bar and hide behind a book until my food came, or my friend showed up.

I could tell Penny anything. Anything. Over the years, she opened up to me about her life, although rarely about her health, which was a source of frustration and sadness as her problems worsened. We talked about our families, each extraordinarily dysfunctional in their own special ways, as dysfunctional families tend to be.

She was the person I could share anything with. I write that with amazement. One time over drinks I told her the worst thing I ever did, a secret that had been skulking in my mind for decades. I don't remember what she said, but what she conveyed wasn't "no big deal" anymore than "wow - you did that?" It was more like "okay, that happened." And with that, I was able to move on.

Penny could certainly register a criticism. She complained about me putting up with my long-distance husband when he had his fits of rage, and couldn't comprehend that from a distance he was my best friend. When I agonized over my relationship with my daughter -- before I knew her son -- she told me I was too involved, again, with the cynical half-grin. And then I saw her with her son, whom she totally doted on. And worried about at least as passionately as I worried about my daughter.

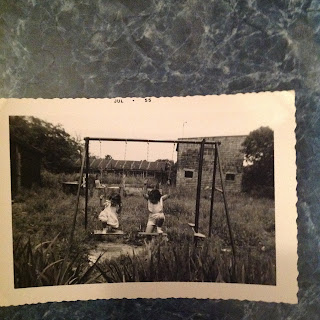

As easy as it was for Penny to talk to others, she was a private person. There were places she would not go with you. She only openly admitted her age to me months before she died. Her health problems were completely off limits. And she absolutely hated when people tried to take pictures of her.

That tiny woman could terrify people. You DID NOT want to refer to her as Miss, Mrs., or certainly, "hon." She quickly and in no uncertain terms informed the individual, whether it was a server at a restaurant or a doctor's receptionist, that "I am NOT 'hon'; I am Doctor Travis." While I cringed for the poor young man or woman taking our order, I was proud of her for insisting that others know she had status.

She never terrified me, because despite her sharp tongue, she was extraordinarily gentle. She worried over hurting people's feelings, for example, when our little lunch group was bursting its seams and she had to let people know not to invite all their friends. She was gentle with me. And there whenever I needed her.

And so, as I was losing her to whatever poorly defined illnesses were incapacitating her, I was aware that I was losing my best friend. She died one short month after my sister, in August. I had lunched with her when I came home from the funeral, told her the sad stories and the funny ones. She wasn't feeling very good, and barely touched her food. She had pretty much stopped drinking, which was even sadder to watch, because she enjoyed her glass of wine and wouldn't have considered a meal without one.

But she still listened.

In very different ways, losing my sister (two years younger than me) and my closest friend (ten years older) has shaken me where I am most mortal. I have learned over my life not to get too close, not to share too much, not to be too vulnerable. I imagine I will not have another close friendship. I am amazed that I was lucky enough to have this one, that grew so easily over the years.

By the way, she would have killed me if she knew I had taken this picture. It turns out it was a risk worth taking.